ABSTRACT:

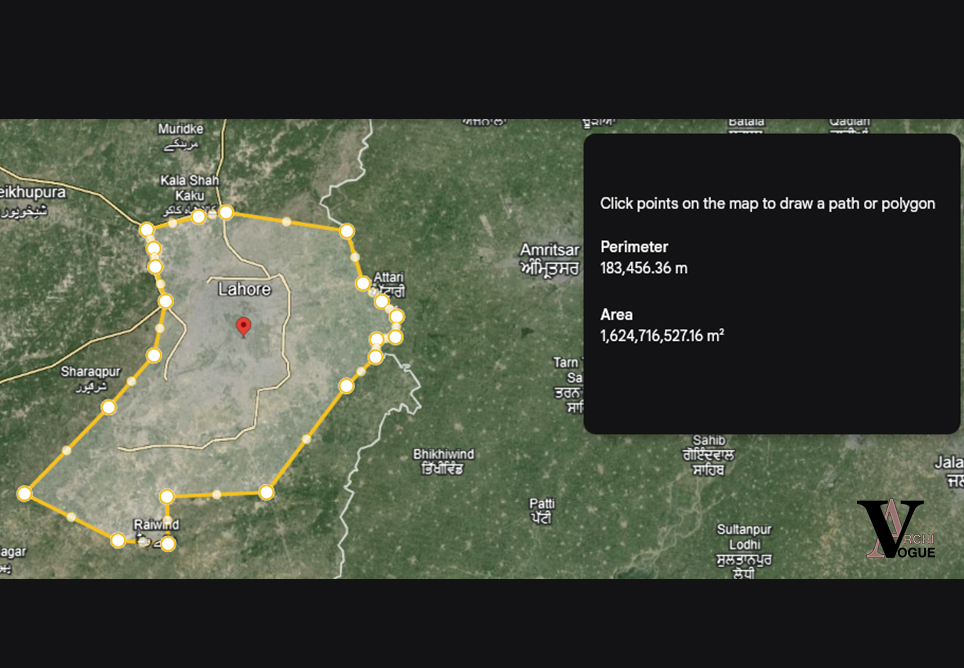

The paper seeks to discuss what history has to say about the modern architecture that was initiated when a lot of criticism could be seen in the late 70’s and early 80’s. Many modernists and ideals were under critical eyes through media, architecture, or theory. There has been a challenge that occurred between the ancients and the moderns while the Modernist movement began in architectural history. An analysis has been generated between two buildings one from Post-modern times (Eastern façade Louvre) and the other from the post-colonial era (Assembly building Chandigarh) to understand the architectural behavior that changed through time. The paper has been divided into three major parts; starting from the background of what makes architects and modernists change their perspective of Modernism and modernity and along with that the history of both the buildings discussed above. Similarly, the second part comprises the building details, its architectural aspects, and its concept. Whereas, the last part is the critical review of both buildings.

Keywords: Modern, Architecture, modernity, Analysis, Theory

INTRODUCTION:

Modernity and Modernism are two different phenomena. Modernism is a movement that arrived in the late 19th and early 20th century in reaction to traditional forms of cultural and social activities. It was developed by the bourgeois during the Industrial Revolution. Whereas modernity is a phenomenon in the development of civilization. Before Modernism, there was a period when modernity started to take place in the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

To begin with the terms, theory and modern both previously came into significance in the late seventeenth century. This term and its variations very quickly became standard in architectural conversations all through Europe. However, modern additionally came into use around this time. Its Latin root modernus first showed up in the late fifth century, though different words in early artifacts were utilized to communicate a similar idea. Its utilization at long last got persistent by the eighth or ninth century, in such edifices as modernistas (of the current day) and moderni (present-day individuals). It was the “quarrel of the ancients and moderns” in the late seventeenth century, that, may promoted modern as an art term. The “quarrel,” an aesthetic and artistic conflict of the 1670s and 1680s, was vital to the development of present-day modern theory. It pitted the individuals who shielded the masterful prevalence of the old-style Greek and Roman periods against the individuals who embraced the predominance of present-day specialists, with their increasingly “contemplated” leads and refined tastes. The “ancients,” to put it, by and large, favored the “ornaments” imaginary in traditional occasions to more up-to-date and progressively current developments. The “moderns,” while recognizing the benefit to be picked up by examining the past, set out to scrutinize ancients for their “imperfections” and looked to enhance them. (Mallgrave, n.d.)

The term ‘architecture’ from centuries revolves around the word ‘art’, the expression of the ideas which every individual portrays through his work with a different school of thought. Looking into the timeline from the sixteenth century till the first century there is a change all around the world while practicing architecture. It can be political or due to religion and even environmental just because of the political background and the thoughts towards the architecture were based on practical systems and the way proportions were perceived was opposite to what Vitruvius mentioned in his ten books of Architecture. The war between ancients and moderns and how we have left are history behind is due to the teachings we have got from our schools. In the mid-century when architectural schools were being established every school had its ideology whether ancient or modern due to which there was a certain link with the history. There were various architects graduating but the difference come when they practice work with their principles. In today’s world, all the buildings are working on the same parameters following the term ‘modern’ architecture because of lack of knowledge and without investigating what we have left in the past.

At the beginning of the rule of Louis XIV, architecture was changed directly inside the classical tradition. Jean-Baptiste Colbert was positioned as the supervisor of buildings, imperial manufacturers, trade, and fine arts in 1664 and had a great influence on the derivation of arts. Several fresh artistic and architectural initiatives of the ruler were under full control of Colbert after that position. He worked on many art projects, but the primary architectural project at that time was the “Eastern Façade of the Louvre” which was under construction. This building was to serve as the urban residence of the new king. If we look into the history of its construction it was the site dated in early medieval times, but undergone a lot of destruction in sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Pierre Lescot in 1546 produced the first master design for the southwest wing which led to the formation of different extensions. Again in 1624 Jacques Lemercier developed a more aspiring master plan and made the building double with the addition of a new central pavilion. The idea was to build southern and northern wings at separate ends and combine them at the eastern end with the new building making a square with an interior court but its construction stopped in 1643 when Louis XIII died and only the basement of the north wing was constructed (Mallgrave, n.d.).

Louis XIV in 1659 took his throne and resumed the construction by the king’s initial architect Loui Le Vau who arranged a new design for the complex. Colbert was unhappy with the design of Le Vau so he secretly started to find alternatives from other architects including Jean Marot, Pierre Cottart, and Francois Mansart. Two important influences were seen on the final product one was for the open colonnade of Corinthian columns alongside the eastern front which wasn’t seen in Le Vau’s design and the other was that the work turned out to be of Claude Perrault the older brother of Colbert’s private secretary Charles Perrault. With more than three hundred years of historical detachment, it was impossible to understand the selection of Perrault but due to the political background of his brother Charles Perrault and Colbert’s desire, he certainly made his existence to the leading committee with the least interest in architecture (Mallgrave, n.d.).

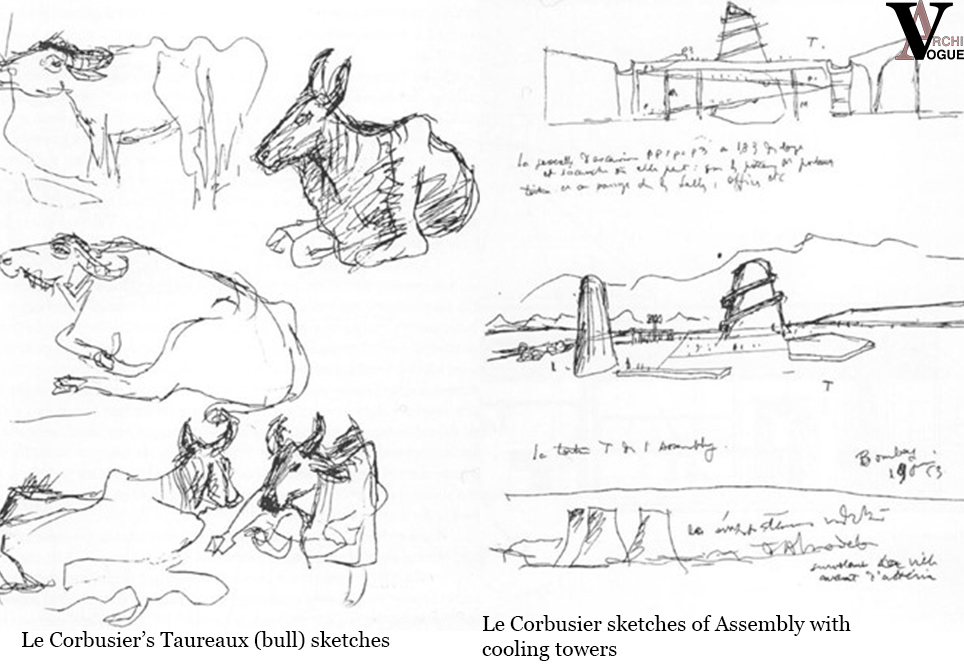

Modern architecture has always reflected a Western inheritance because of its origin which lies in Western history. Origins are not just the only ends or the only way of deriving identity and ownership but they can be equally valid in other ways such as adoption, appropriation, and participation. In the Nehruvian vocabulary, modernity means the effort to cope up with the West but with aggression. The orders of that day were new cities, airlines, steel plants, iron, and large hydroelectric dams. To build the edifice of modern India educated and westernized elites were called whereas Le Corbusier and Nehru decided that Chandigarh had to be a ‘modern city’. Chandigarh’s modernism was not just as modern architecture, or modern Indian architecture but as a non-originary Indian modern architecture. The question is what is “Indian” and what is “modern”? The term ‘modern Indian’ is particularly challenging in the domains of the Indian cultural context. The word ‘modern’ in India not only indicates ‘contemporary’ but also imitates Western, superior, and better. In postcolonial India modernity certainly implies a break with its history and the dominance of the West. Today in India, to be modern is to praise the West (an outsider) which is now the necessity (inside) for the progression signifying as ‘Outsider-inside’. Le Corbusier referred to India’s living “under the sign of the Bull” which also relates to the statue of the Nandi bull established outside the temple of Shiva which he once had seen. Le Corbusier had copied the impression of a bull which may connected to the ancient Indus Valley civilization. In Hindu cosmology, a family of cows was honored and in India Le Corbusier’s aesthetic fascination was to draw animals. Ultimately the design of Assembly had an impact on (Taureax) Bull discovery. (Vikramaditya Prakash, n.d.)

This paper will be based on a critical analysis of two post-colonial buildings built in two different zones of the world keeping in view the background of or history of modernity and Modernism. For that, a mixed method approach was adopted for collecting the data because the paper was written during the Pandemic COVID’19 where it was unable to approach to the data directly. Most of the theoretical data was obtained from the research articles, thesis reports, Books, and journals which were available online or by approaching any online concern.

EASTERN FAÇADE OF THE LOUVRE MUSEUM:

CLAUDE PERRAULT

It is not promptly evident why the eastern facade of the Louver Museum, primarily a royal residence, was considered among the most significant design works in France toward the end of the seventeenth century. There is an incoherence nowadays between the magnificence of the structure and the familiarity and littleness of the space before it, the Place du Louver. At first, it planned to be the principal, official entrance to the castle, the surface returns close contemplation, notwithstanding its un-exalted place today. It is a principal incident of the thorough plan bond in a French style, a worshipped model for the resultant imperial residence structure, and a landmark connected with the causes of revolution in engineering.

The Louver as we are probably aware of it today came about because of a progression of extensions of more than 800 years. It ought to be recollected that, though the Louver is currently the focal point of Paris until the eighteenth century it was at the city’s western end. Beginning in 1190, King Philippe II developed a strengthened weapons store on the correct bank of the Seine River. In the fourteenth century, Charles V changed it into an illustrious habitation. In the mid-sixteenth century, Francis I’s draftsmen wanted to extend the castle into a progressively open Renaissance structure. His replacements, particularly Kings Henri IV, Louis XIII, and Louis XIV kept creating ever more fantastic plans, transforming the castle into a pointless building along the waterway. Louis XIII started the development of the eastern square known as the Cour Carrée (square yard) in the seventeenth century, an emblematic signal of connecting in the direction of the downtown areas from its fringe (above). Its exteriors were intended to propose the association of the ruler to his main city. By the center of the seventeenth century, nothing over the earth was left of the medieval fortification or the fifteenth-century castle. At long last, during the 1660s, the east wing was reconsidered as a self-important imperial access to the entire structure. (Dr. Paul A. Ranogajec, n.d.)

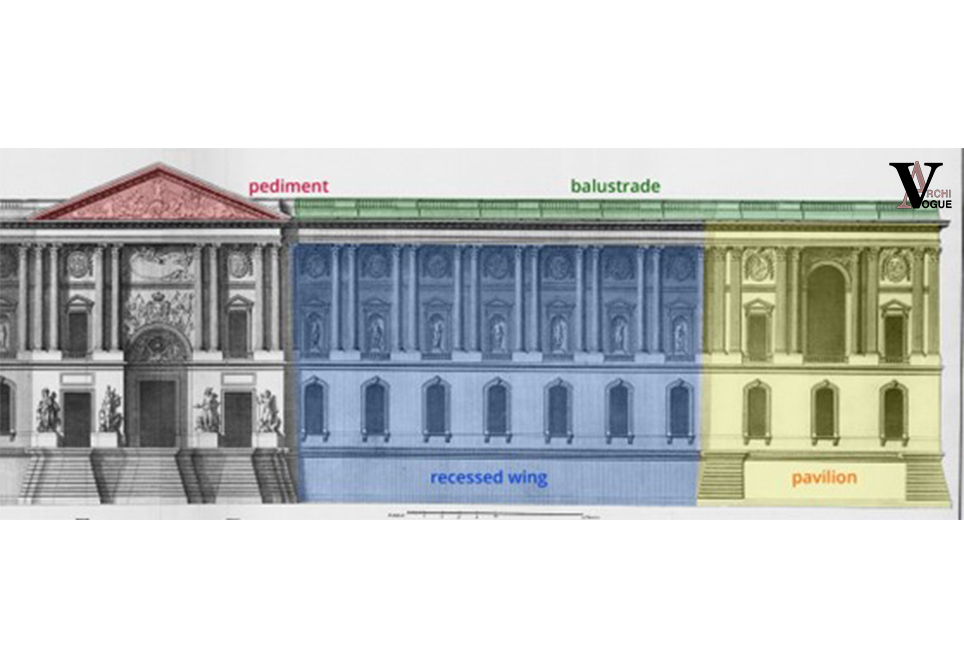

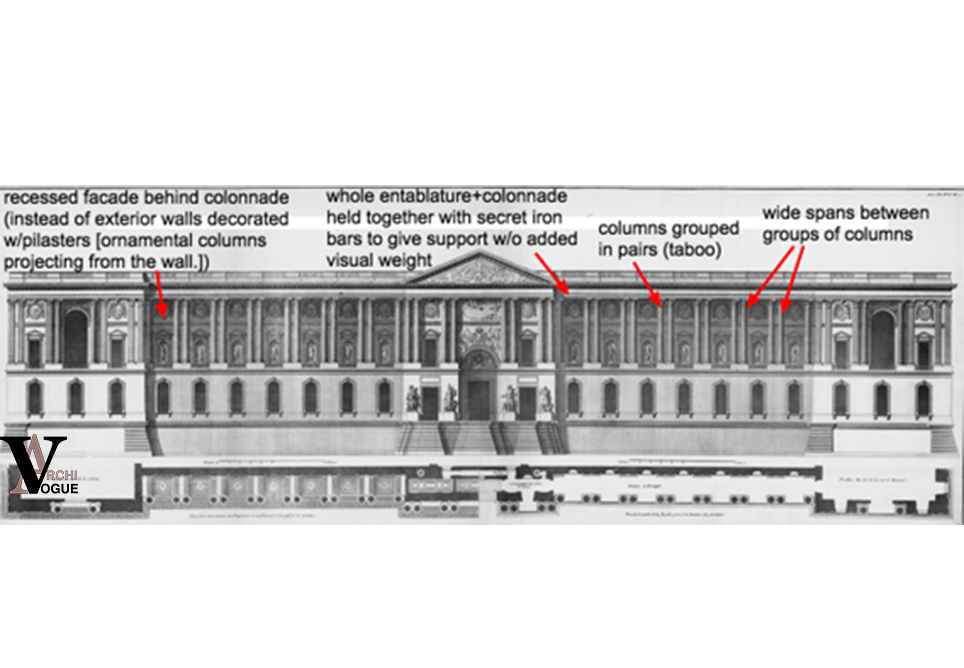

The extended facade tails the five-section example of French fortresses: two structures, one on every end, with depressed wings and a central arrival crowned with a pediment. In any case, the structures just marginally projected onward from the wings, and they don’t arise higher than them. Just the short triangular type of the dominant structure’s pediment breaks down the rigorous horizontality of the roofline, stressed and relaxed with a balustrade (a nonstop railing), which was a most loved theme of Le Vau’s. The end pavilion is carefully completed with a small relief design, analyzing Roman triumphal arches. Structured as a strong base, the lower floor utilizes windows like prior ones at the Louver, making visual progression with the more seasoned segments and offering outwardly solid support for the corridors above. (Dr. Paul A. Ranogajec, n.d.)

Along with the horizontality of the facade, the paired columns of the identical porticos (covered walkways, here along the colonnades, or depressed wings), mark a beginning from prior magnificent buildings in France. The Corinthian columns advise a persistent, dependable mood to the complete facade. Established before the deep porticos, the shadow and light of the columns make visual advancement. Furthermore, there is a variety in the employment of the columns: at the center pavilion and in the colonnades they are unsupported, yet in the direction of the end pavilions they convert into coupled columns around the central windows and pilasters at the exterior ends. Their somewhat slenderer ratio distinguished from most Corinthian columns makes up for the more wide range one sees in the doubled motif. (Dr. Paul A. Ranogajec, n.d.)

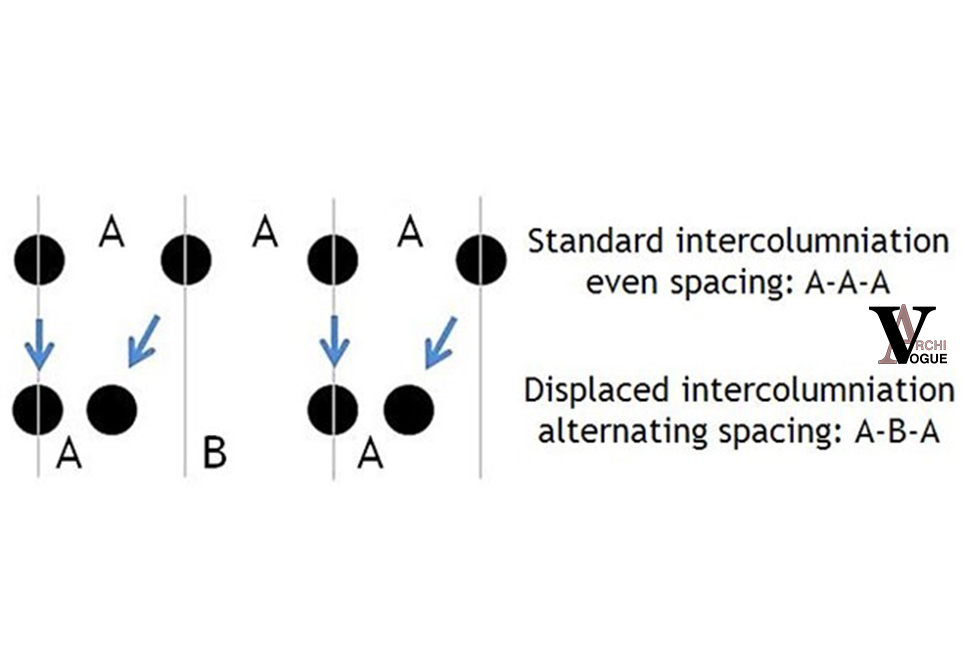

The most alarming part of the design at that time was the paired columns. The subject of the arrangement of the columns (called intercolumniation), was one on which Vitruvius and Renaissance architectural journalists had invested a lot of time. A figure published in Claude Perrault’s translation of Vitruvius, Les dix livres d’architecture de Vitruve, clarifies how the colonnades were planned. Perrault demonstrates a progression of four columns set apart uniformly in a row. This is the normal intercolumniation of an antiquated sanctuary. To achieve Louver’s colonnade design, Perrault shows how every other column is displaced toward its neighbor to one side. (Dr. Paul A. Ranogajec, n.d.)

By dislocating partial of the columns to make the doubled column design, more prominent prominence is put on the spaces between the columns: that is, the huge space between individual pairs of columns (B) and the restricted space among the segments of each pair (A). This makes the vibrant graphical beat, A-B-A, rather than the more static A-A-A.

As indicated by Perrault, this plan, bringing about more wide than normal scattering (dégagement), is an authentic development of a 6th kind of old-style intercolumniation. Vitruvius, the antiquated Roman architectural expert, had observed five perfect kinds of column positioning; Perrault assured that the Louver was an additional suitable kind to modern French flavor. He opposed that while the people of old favored firmly spaced columns due to some limits to the structure of buildings working in stone. The French, with their custom of lighter, progressively open buildings getting from the Gothic houses of God of the late Middle Ages, lean toward wide spacing. Perrault, in any case, never talks about the way that the facade consumes a huge amount of iron reinforcement, without which structural forces would tend to push the columns outward. (Dr. Paul A. Ranogajec, n.d.)

Perrault designed the eastern façade according to the classical architecture rules. There was a switch from old cosmic orders at the end of the 1500s to the new mechanical world. It seems to have s revival of classical architecture from two styles; the Baroque (a high-spirited and impressive style with a lot of ornamental details) and Rococo (more elaborative than the Baroque style). A clear rational development in France after the establishment of academies. The style was associated with serenity, perfection, and limitations which were defined by its boundaries, harmonious proportions, and symmetry.

ASSEMBLY BUILDING, CHANDIGARH:

LE CORBUSIER

As proposed by the master plan Le Corbusier designed the capitol to dominate the city in its earliest stages. An important part was to be played by the secretariat to achieve dominance. The building was a long and low-rise structure positioned almost at the edge of the city. The Assembly, the Governor’s Palace, the High Court, and the Open Hand would also be visible at different depths of the city because there were no evident obstructions. Similarly city would also be visible from the Capitol which shows that the Capitol at least enjoyed a visual relationship with the city without any hindrance. After the discovery of Taureaux, the composition of the capitol was critical in terms of the appearances. Le Corbusier always used sketches that were drawn on-site to make some critical design decisions.

Quite a bit of Le Corbusier’s attention over the ensuing years was dedicated to the capital complex, in which he permitted his thoughts on fantastic articulation free of restriction. Like Lutyens, he took in his exercises from the Mogul convention, in the arrangement of profound terraces, sentimental roof-scapes, and water. The ‘parasol’ improved against water and sun fused a conventional picture of power, and turned into such a mutual element at Chandigarh, repeating on the head of the Governor’s Palace. The Secretariat, changed into the titanic expose of the Parliament building portico, turning into the type of the justice basilica itself. In reality, the beginning of his monumental vocabulary appears to have included a massive accomplishment of abstraction wherein gadgets from the Classical convention like the grand order, and the portico were intertwined.

with Le Corbusier’s nonexclusive arrangement of structures in concrete the brise-soleil and so forth. Thus, hybridized with Indian gadgets like the ‘chattri’, the trabeated patios, overhangs, and loggias of Fatehpur Sikri. This architectural language, wealthy in references and relationship of an open organized kind, was submerged with the craftsman’s private cosmological topics – the dream of water dowsing and sprinkling over enormous solid rooftops and surfaces, the picture of the sun’s way at the solstice and the equinox attached to the monster lighting tower of the Parliament, and the inquisitive ‘Valley of Contemplation’, embellished with signs speaking to various parts of the planner’s way of thinking. (Willaim J.R Curtis, n.d.)

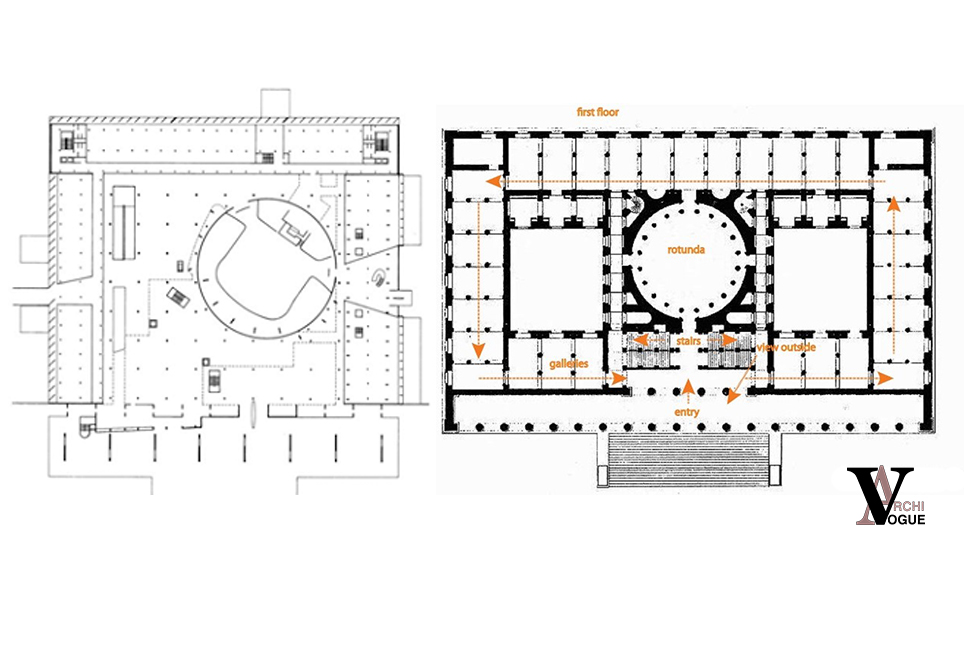

The Assembly chamber was just a large auditorium with a skylight for years because Le Corbusier concentrated on the eastern and western façade of the building. In the beginning, the Assembly was conceived as having the same aesthetic language as the High Court building. The blank side of the High Court façade was split from the middle and extended to accommodate a gigantic box they would have been the same because their side elevations were also the same. The Assembly building itself was stacked with imagery and advanced with antiquated references. It was structured as an enormous box with a grid of columns inside it. Drawn closer through a portico along one side upheld on rib-like wharfs, with the enormous ‘objects’ of the principal Assembly and Senate set down into it. These were made obvious in the external thoughts the sculptural roof-scape structures, an inclined pyramid for the Senate, and a unique channel-like shape for the fundamental Assembly. Tough cement, with all the signs and improvement of harsh workmanship, was utilized all through; the burning atmosphere before long included its layer. If the outcome resembles a giant, grave, and noble ruin, this was most likely proposed: one has the vibe that these structures probably remained on this level for quite a long time. The sides of the box were punctured by the profound cut. Revised shadows of brise-soleil while the fundamental facade gave a motion of impressive custom. The way of talking was continued on the interior where one remained behind the blasting warmth and the spiked shadows to enter a cool, peaceful universe of translucent chambers ascending to a dark soffit. The light sifted in from the sides of this floating component to uncover a space the antiquated Egyptians may have honored. The mushroom bolsters looked as though hypostyle models had brightened them. Concrete was here invested with the thickness and gravitas of reduced and cleaned stone. With the amazing volume of the extraordinary channel containing the Assembly sliding into it with the rising groupings of inclines and the immense floors, this was a certain showing that monumentality had not been passed on in the modern era. (Willaim J.R Curtis, n.d.)

The Assembly room itself was well-lit. It did not have the charming environment of the hypostyle around it and its round floor plan was to some degree at chance with the capacity of pleasing a popularity-based, political discussion. In any case, it is fascinating to test the beginning of the ‘channel’ idea as this gives signs concerning the way Le Corbusier interpreted pictures and thoughts into structures. In the earliest phases, the Assembly building was a nearby relative of the Hall of Justice inverse: an enormous box under a monstrous parasol in concrete. By steps, the topic of the portico rose normally from the outflow of the rectangular trabeation inside. At this stage the principle chambers were lowered in the case as two organ-molded rooms encased by freestyle bent parcels set into the network of supports. A key advancement was made in mid-1953 when the planner started to imagine the sensational chance of sun and twilight entering the rooftop; there were even ambiguous traces of ‘nighttime celebrations’ and ‘sun-based festivals’. It was then that the possibility of the light tower, an article inside the greater object of the box – started to rise, its structure mostly propelled by the hyperboloid state of intensity station cooling towers (surely ventilation concerns may have set off the similarity). In the arrangement of a stack-like structure in the focal point of a box. One perceives an essential Corbusian tendency for the mind-stretching out back in any event to the extent the lands of the 1920s. (Willaim J.R Curtis, n.d.)

Le Corbusier may have been influenced by the arrangement of Schinkel’s Altes Museum in Berlin, where the theme of the colonnade, network, and circular form had been expressed with extraordinary rationality and power. The decision of these structures far rose above utilitarian worries (truth be told, the arrangement was rarely completely practical): they emerged as much from the craftsman’s point of making such a cutting-edge proportionate to the dome – a token of state authority and rule. Among the early sketches, some demonstrated the Chandigarh stack close by an area of the dome of the supreme church of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, and others indicated the sun flowing down through the top in a way reviewing the Pantheon.

CONCLUSION:

CRITICAL ANALYSIS:

As discussed above Perrault translated the Vitruvius ‘Ten Books on Architecture’ and he was much influenced by the theory he was using for architectural building. Perrault background was in sciences and as he was not professionally an architect, he had vast knowledge about mechanics no doubt it can be seen in the structural solutions of colonnades which are hidden under the grid of iron bars holding the brickwork together in an elaborative manner. We can see a revolution in practice and theory perfectly overlapping together in the Louvre proposal and the translation of Vitruvius as it represents the unusual moments in the history of Architecture. Moreover, Perrault has observed doublings in Vitruvius’s text everywhere and often emphasizing contradictions that were tried to overcome before.

The question or contradiction that can be proposed is the doubling or paired columns in Louvre design or it can be featured by single columns also? As far as Perrault used these paired columns seems like it was for the structural support to cover the long length of the façade. But it is just for structural purposes only? It can be a political agenda also that can work well for the monarchy as an architectural face. Perrault tried to follow the Vitruvius traditions of order and symmetry in the façade which may not be as contradicting but it acknowledges the ancient’s authority by violating the influences of the unknown in his design. To understand the role of colonnades in his design the only key is ‘Symmetry’. Symmetry is the only tool that can convert a single column into a double through a vertical axis so in the Louvre façade we can see a vertical line drawn in between the paired columns. Perrault tried to represent a potentially self-perpetuating system of construction in his design. The propagating of columns through symmetrical axes explains the persistence mapped on the entire colonnade.

He used a word as ‘Intercolumniation’ in his design which may emphasize the space that is in between the paired columns and relates to the translation of “Vitruvius’s ten books” where there is a footnote related to intercolumniation of the Louvre Museum façade colonnade that it “appears as an exception to ancient rules” and called it as “the invention made at the Louvre”. Perrault dared to break the symmetry of intercolumniation by modifying the segments in the columns. Hence the paired columns in the Louvre show the variation of distances rather than showing an accumulation of elements in it. It is more like an illusion to the viewing eye because columns are not added but they are displaced because it is showing as a system of difference between the columns.

In the quarrel between ancients and moderns, Perrault wanted to conclude this masterpiece as a modern statement by making a clear difference between the spacing of columns. Ancient temples had very narrow spacing that only one person could pass at a time but by creating generous intervals he put it as an ‘Advance-Element’ in favor of the French. We could conclude the argument in a way that Perrault in ‘Louvre Façade’ tried to demonstrate both ancient and modern architecture by adding small spacing between the columns and long intervals in between the paired columns calling it “modern-degagement”.

In the effort of observing Le Corbusier’s architectural style, concept, and language there is one common factor in every building which he designed that he demonstrates ‘Power’. He shows the power of the city or a county through the visual aspects of any of his buildings. His focus has always been on the facades or skylines something that can be observed from the naked eye. Especially in India, his work is mostly famous for the visual language of the buildings which might fall under the great architecture aspirations. Certainly in the beginning, Corbusier’s concept drifted in the Assembly Building where he tried to work on the function of the building and its interior rather than the entrances or the façade of it. But later he was able to create an impact by adding elements in the building structure.

When Corbusier wants to create a style statement in a building he creates a drama with the skyline mostly. Similarly, in the Assembly building, three elements can be observed from the facade on the roof; the pyramid, the hyperboloid, and the cooling towers, all the three playing against the sky. As discussed above there seems to be a similarity in Schinkel’s Altes Museum plan with Le Corbusier’s Assembly building plan. Such an analysis of both plans could reveal the transformation that how the same spaces have been utilized differently. A few spaces that were to be discussed are; stoa (classical portico) in Schinkel’s plan was changed into a huge, gigantic porch, then there is a U-shaped block developing an interior hall with three separate blocks joining with the hall. The major transformation in plans can be seen when there was displacement in the central circular volume in the center. In Schinkel’s plan, it is in the center with its own interior and exterior walls around it but in the Assembly plan, it could be seen as displaced on the right side of the plan.

Observing a bit about the façade of the Assembly building, on the roof there is a paraboloid cut to formulate a plane parallel to the earth’s axis which is oriented towards the north-south and curving blades are placed on the top of the roof which later were straightened. So these three parabolic shapes are accompanied to demonstrate the sun’s moment through the sky. All this effort was made just to show the Taureaux discovery in the building. But all these elements made the building look in vertical composition rather than horizontal. Its hyperbolic paraboloid makes the highest point in the building and is placed on the most important part of the elevation. It seems to look like the Assembly building has lost symmetry which can be seen in the High Court building. The concluding remarks would be that the Assembly building lost its uncanny aesthetics because of the lack of exterior structure and the paraboloid establishing a questionable vertical axis. In this way the aesthetical journey of the building through Taureaux’s discovery failed as Le Corbusier called this discovery a “re-discovery of the vertical axis” but as seen it got transformed from horizontal into vertical.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Dr. Paul A. Ranogajec. (n.d.). Claude Perrault, East facade of the Louvre. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance-reformation/baroque-art1/france/a/claude-perrault-east-facade-of-the-louvre

Mallgrave, H. F. (n.d.). MODERN ARCHITECTURAL THEORY.

Vikramaditya Prakash. (n.d.). Chandigarhs Le Corbusier.

Willaim J.R Curtis. (n.d.). Modern architecture since 1900.